Finding a Creative Spark Within Solitude

Through the lens of work from writer Olivia Laing and artist Edward Hopper, we explore how solitude can turn us into keen observers and fuel creativity.

As creatives, our inspiration often comes from external influences like travel, gatherings within our community, or new perspectives that emerge through conversation with peers—but don’t overlook the internal source of that spark. We know how to make the most of it when it happens, but here we’ll explore how to connect to it on our own.

“Humans are uniquely social. We spend the majority of our lives with other people,” Dr. Steve Cole, Professor of Medicine and Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences at the UCLA School of Medicine, says. “Most of what we do, we get done in concert with other people.” But there are upsides to solitude, particularly for creatives. The pang we feel at the absence of human connection makes us keen observers, alert to subtle details that normally go unnoticed. Often this is uncomfortable—the lonely brain is primed to identify threat and social rejection in even innocuous encounters—but it can also lead to creative breakthroughs if we accept it.

***

Our species’ survival is based on connection—we are anything but solitary as humans. As a result, loneliness, or the acute want of social interaction and kinship, sets off primordial alarm bells, Cole says. Loneliness “keeps us longing for one another, keeps us able to function effectively in these big groups,” he says. “You can think of it as the same adaptive motivational strategy for this aspect of our lives that thirst would be to keep us hydrated and hunger would be for keeping us fed.”

Edward Hopper, an artist frequently associated with loneliness thanks to his depictions of urban spaces punctuated by solitary figures, was himself quite isolated, says Jennifer Patton, executive director of the Edward Hopper House Museum in Nyack, New York. “He didn’t like many people and most people didn’t particularly like him,” she says. “He wasn’t a man of social graces.” But he also saw what other people didn’t, obsessively drawing scenes and details that most would pass without noticing.

The period she spent living in New York was an intensely lonely time for writer Olivia Laing. To cope, she found herself drawn to art that explored the emotion, notably Hopper’s masterpiece Nighthawks. “The artists I encountered in the lonely city helped me not just to understand loneliness, but also to see the potential beauty in it, the way it drives creativity of all kinds,” she writes in The Lonely City, a love letter to the “strange and lovely state.”

To find ourselves in this state—even if by design as a solo creatives—can be uncomfortable. But there are ways to manage the resulting loneliness including seeking out, as Laing did, its silver linings.

Be forgiving to yourself

Cutting physical ties not just to loved ones, colleagues, and friends, but the communal feeling of moving through a crowd is painful. Technology mitigates this somewhat—thanks to a creative use of Zoom, Hangouts, and text, it’s possible to keep in contact with friends and collaborators.

But digital tools are a poor substitute for physical community. It’s difficult to read face and body language over pixelated screens, harder still to achieve the sense of togetherness engendered by in-person experiences that allow us to share the same physical reality. And screens don’t allow for touch, which is a “surprisingly powerful form of communication,” Cole says. Physical contact, from friends, loved ones, even acquaintances and strangers, has the ability to lower cortisol levels and ease anxiety. “That is one of the fundamental cues our body uses to read whether we are well—whether we are linked up with other cells in the metaorganism of our community,” Cole says.

“Thanks to a creative use of Zoom, Hangouts, and text, it’s possible to keep in contact with friends and collaborators.”

The act of simply identifying this lack—and the impact it has on one’s ability to focus and create—can help. Personally, I also take solace in the knowledge that the scatteredness and sadness I feel from not just missing family or friends, but moving unworried through a crowd, is universal and worth acknowledging.

Work towards something larger

One of the best ways to combat loneliness is the pursuit of a larger goal, ideally one that requires teamwork and collaboration, Cole says. Focusing on a shared vision helps disrupt the lonely brain’s self-critical, destructive loops, allowing us to let our guard down and reintegrate ourselves into the social fold.

“Through digital tools, we can continue to brainstorm with colleagues and work together towards collective deadlines and goals.”

Technology makes it possible to do this remotely. For many of us, work is one outlet. Through digital tools, we can continue to brainstorm with colleagues and work together towards collective deadlines and goals. Or kick off an ambitious side project to work on collaboratively within your community that serves a greater good. Having regular check-ins around a long-term project is one way to feel connected beyond your day-to-day.

For many, art serves as a motivating larger purpose, if a solitary one. As Laing recounts in The Lonely City, she wasn’t happy during the solitary time she spent in New York, but the experience, while uncomfortable and sometimes painful, was illuminative, inspiring connections and insights she’d never had the space to consider before.

Pay attention

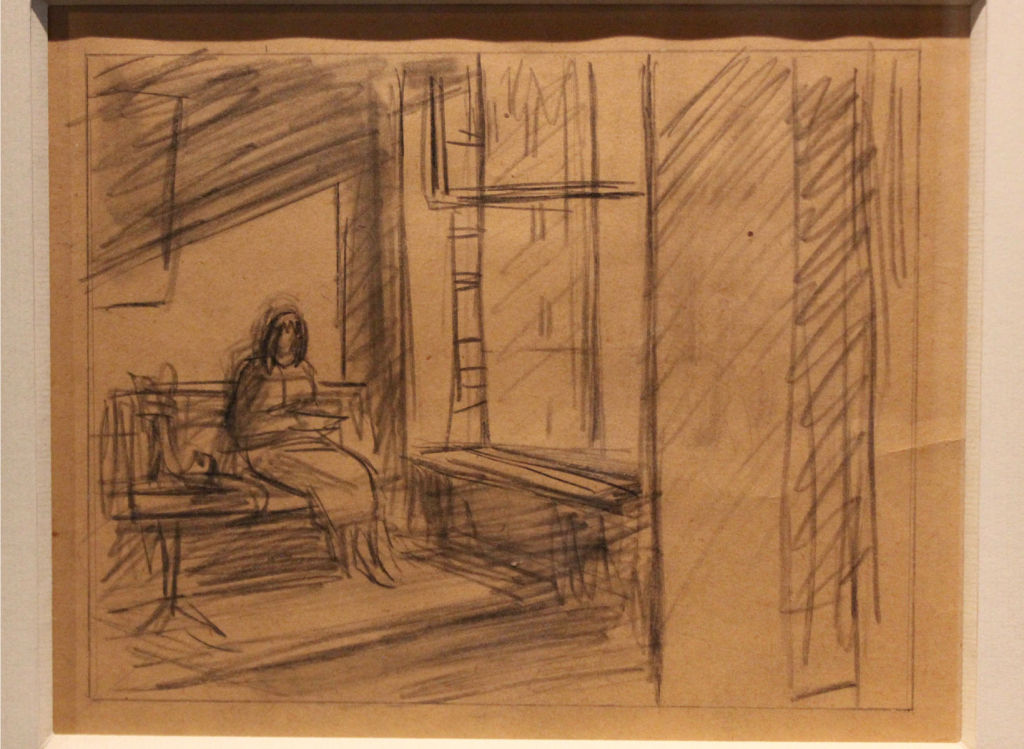

Growing up, Hopper traveled through his small hometown of Nyack on foot, observing. (Upon his death, Hopper left the Whitney Museum thousands of his sketches from this time—of boats, people, hands, cigarettes—an endless procession of captured details.)

Original Edward Hopper sketch courtesy of Edward Hopper House, photographed by Liv Johnke.

Later in life, he traveled further afield. This included glamorous trips abroad, like a series of solo visits to Paris in the early 1900s. But usually, it was more prosaic. In New York, Hopper liked to ride the subway. “He was always at eye level—if he could sketch on the L train, he would,” Patton says.

“Those of us lucky enough to self-isolate at home are left with a rare commodity: time.”

In the past few weeks, Patton has found herself taking in more of her surroundings like the artist whose work she spends her workweek with. Her days, once consumed by the mad rush of getting her kid to school and getting herself to work, are far quieter. It’s spring in the Hudson Valley, and for the first time in a long time, she has watched the magnolia and cherry trees bloom. “I’ve never noticed the weather as much as I do right now,” she says. “I’m not going to the grocery store that often, I don’t have errands to run. Wherever I choose to go to get fresh air, it’s not so much about why I am going there.” The lack of purpose leaves space for observation: the light, the temperature, the architecture, like a Tudor house down the block she never noticed before.

A writer friend has experienced the same thing; as her world has narrowed to her apartment and immediate neighborhood, she’s started to notice architectural details she used to gloss over in the rush to get elsewhere. Once home, she investigates their histories, like the well-maintained mansion that used to be owned by a rich piano manufacturer. Parameters aren’t always bad for revealing new directions of inquiry. Her life is more contained, but the questions and sparks keep flowing.

By Laura Entis Illustration by Andrea Manzati

Source: Adobe 99U