Emoji: documenting the design story

Standards Manual’s latest crowdfunder charts the emoji’s meteoric rise from a series of simple picture characters created in Japan in the 1990s to a global phenomenon. The publisher’s founders Jesse Reed and Hamish Smyth tell us about the history behind the original emoji, and the universal appeal of the humble set of icons.

Design Week: Tell us about how the original emoji came about.

Jesse Reed: The basic history goes like this – NTT DoCoMo is a large Japanese telecommunications company that was founded in 1991. Between 1991 and 1999, the company developed a revolutionary software called “i-mode”, primarily used for pagers and emails. A feature of i-mode was a pictorial component, and this is when the heart emoji was introduced to its interface. Shigetaka Kurita was an employee at DoCoMo working on the i-mode team, and in 1999 he was tasked with expanding the collection of “picture characters” (in other words, the emoji) into the i-mode software.

Kurita was limited to a 12×12 pixel grid, which was dictated by the screen technology at the time. Each emoji had to fit within this framework and there were no shortcuts. Because the grid is an even number, there is no way to actually centre any of the symmetrical emoji. This was a challenge that Kurita had to overcome during the design process.

Each emoji was a representation of an object most commonly found in Japanese culture. Kurita credits magazines and common street symbols, among other things, as a source of inspiration for the chosen emoji. He developed 176 emoji in approximately five weeks, and they were released immediately. There were no focus groups or testing, they simply wanted to see what would happen. The rest, as we all know, is history.

DW: Why do you think it took Western countries so long to catch on?

JR: I guess it’s like anything else that we don’t catch on to from the East, or other parts of the Western world for that matter. Why does Japan have taxi cabs with back doors that are opened by the driver, but the US doesn’t? Because Japanese people are so polite that it would be unthinkable for them to open their own door during their service. It’s specific to their culture.

I think emoji is very similar, and again, closely-related to Japanese life. Emotion and expression is arguably more intensified with a conversation in Japanese than it is in English. So when texting became a normal way of communicating, the lack of emotional impact was lost. They figured out a way to resolve the lack of additional expression with the use of pictures, and it worked.

We can’t speak for all of the Western world, but I would say there’s a fair bit of fascination with how other cultures communicate and the nuances of contrasting lifestyles. We’re a global society now, and that’s because we’re connected by the internet. It sounds so obvious that companies like Google and Apple would include emoji in the operating systems, but it takes a critical mass to influence that shift. Enough people were downloading apps to use emoji, so it was the natural next step – 10, long years later, that is. Maybe one day, emoticons will be cool again? ¯_(ツ)_/¯

DW: You’ve described the design of the emoji as an “accidental masterpiece”. Why did you choose it for your next project?

JR: The idea was brought to us directly by Kickstarter. DoCoMo had approached someone at Kickstarter about doing an app that would include all the original emoji, and it was also at that time that the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) acquisition was on display. MoMA had too many things going on at the time so Kickstarter asked if we were interested. We had never done an app before so there was a slight hesitation, but we asked if DoCoMo had any sketches or drawings from the original set and they did. Once we saw Kurita’s original design process, we instantly thought this would make a great book.

DW: What are you planning to include in the book?

JR: Emoji will open with an introduction by Kurita, and Paul Galloway and Paola Antonelli from MoMA – who were responsible for the museum acquiring the designs – will also write an essay for the book. This will focus on the historical context and social relevancy of the emoji.

The bulk of the book will be the 176 emoji in their original form. Each emoji will be displayed on a single spread, including the colour version at an enlarged scale and full-size (how it would appear on a phone screen), as well as the emoji placed on its 12×12 pixel grid to show the nuances of each design.

The book will also include the original thumbnail sketches from Kurita – a particularly fascinating and, from our knowledge, rarely seen piece. It comprises a sheet of paper full of small emoji sketches, very roughly drawn and put together. It’s essentially the master idea-mapping chart for when Kurita and his team were deciding which objects to include. Lastly, we will also be including the extended set of 76 emojis that was developed by DoCoMo’s team after Kurita left.

DW: Tell us about the design of the book.

Hamish Smyth: When we went to Japan to meet Kurita, we also spoke to printers there. We decided on many of the specifications, some with a nod to typical Japanese techniques. The book will be enclosed in a PVC jacket, a typical method in Japan, with the title screen-printed on the jacket.

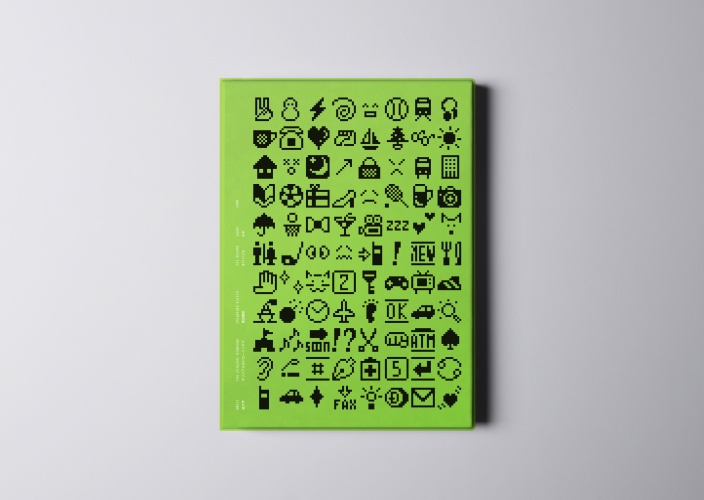

The white hardcover boards will be raw, with all 176 emoji screen-printed in black – half on the front, half on the back. The inside of the book is interesting for us, because this is the first time we’ve designed a dual language book. That comes with its own challenges, but we’ll be keeping the design very simple and in line with our previous titles. After all, it’s all about the design we’re showcasing, not our own creativity. We like to get out of the way.

DW: What do you think is the secret to the mass appeal of emoji?

HS: I think the secret to emoji’s success lies in their simplicity. The original emoji had a very limited canvas of 12×12 pixels to work with, so 148 pixels total. That constraint was due to screen resolution, but also data transfer rates of that period.

Today, an emoji might be designed with vector tools (effectively an unlimited resolution) and will end up measuring at least 256×256 pixels. That’s over 65,000 more pixels to work with. But like any great logo, the simple ones are always the best. It’s more difficult to convey an idea in the simplest way possible, and that’s what Kurita was able to achieve.

Today’s emoji are more nuanced and detailed, to the point that we have dozens for subtle differences in facial expressions – but there is something so pure and refined about the original set that we were drawn to as designers.

DW: What do you think the future holds for the emoji? Will it eradicate the need for words altogether in the not-too-distant future?

HS: This is actually a common misconception about emoji. Their original intent was to supplement words and help convey emotion, not replace them. When we write, emotion can become lost, or the emotive intent of a message can get confused. Emoji was invented to help solve this problem.

As the saying goes, a picture says a thousand words, so using pictures with words helps add to their meaning. When emoji launched in the West, a lot of people thought the idea was to replace text. Some people still try to use it this way, and it certainly can be used as a replacement to text for simple ideas but it’s not supposed to replace text all together.

In a way it’s an evolution of written language, which welds together the very first primitive, symbol-based communication that humans used with digital text communication. We’ve come full circle, which is pretty cool. And that’s why we think this is important work worth analysing and preserving.

For more info about Standards Manual’s crowdfunding campaign to publish the Emoji book and accompanying app, head here.