Why the creative industry needs to start talking about men's mental health

In an eye-opening interview, Ben Oates and Paul Drake of JDO offer the benefit of their experience regarding men's mental health.

Held this year on 19 November, International Men's Day offers a chance to promote positive male role models, focus on men's health and wellbeing challenges, improve gender relations, and create a world where boys can be safe and grow to reach their full potential.

But what does this look like from the perspective of the creative industries? What are the challenges we need to face up to, and what are agency leaders doing on the ground to solve them? To mark the latest International Men's Day, we sat down with two studio heads from award-winning brand design and innovation agency JDO to find out.

In our frank and honest discussion, Ben Oates, principal and group creative director, and Paul Drake, founder and creative director, talk about showing vulnerability, compassion for others, and understanding as agency leaders.

They also share their personal experiences leading and running a rapidly growing and constantly evolving agency, their views on the importance of mental health, the pressure men face in creative careers, and what needs to change.

Feeling lost

Making sweeping statements about an entire gender, whether male or female, is fraught with difficulty, of course. But as a starting point, Paul thinks it's important to be realistic about how at least some men are feeling right now.

"The time when it meant something to be physical and strong as a bloke when we all lived in caves and might be attacked by lions and such, that's all gone," he begins. "Whilst most men no longer have jobs that demand that – that internal need to be the alpha, the protector, the defender, the breadwinner – it still lingers, not only in the deep recesses of our psyches but in what's been passed down generation to generation. Today, the idea of what a man is supposed to and allowed to be is shifting, and that's liberating, but it's also confusing. I think a lot of men are a bit lost."

He's not suggesting society swings the other way and is keen to distance himself from the alpha-male rhetoric propounded by the likes of Andrew Tate. But at the same, he feels it's important we acknowledge the problem. "It's probably part of a reason that three-quarters of deaths by suicide are men and that suicide is the biggest cause of death in men under 50," Paul points out.

Internalising issues

The issue is compounded, Paul adds, by the fact that men tend to bottle things up. "I know this strays into stereotyping, but I think it's undeniable that women talk more to each other about their problems and stuff that's going on in their lives," he says. "And what I've observed from my wife and other women I've known is that they'll talk their problems out. So they've got some kind of support network around them they can go to.

"I don't think blokes have that," he continues. "Blokes like to talk about other stuff when they see their mates. And maybe there's also a slight reticence to show that you're not confident and struggling." He adds that this dynamic is so powerful that, as a whole, men aren't even comfortable spending time together one-on-one and prefer to hang out in groups as a result.

This bottling up of problems can be a toxic issue in the design industry, which is already so full of pressures. In particular, Paul points to the fact that creative work is never 'done' in the way that it is in more traditional jobs.

"My dad was a builder and a carpenter, and he looks at what I do and thinks: 'That's not hard work,'" Paul explains. "But actually, I envy him in a way. For him, you started, you finished, and you walked away. In our work, there is no finish. There's almost no right or wrong. So you're always doubting. You lie in bed doubting and worrying about everything and stuff people don't even see."

Roller coaster of anxiety

This is compounded by the general anxiety that riddles the profession. "You're only as good as your last job," says Ben. "And so the roller coaster of pitching, winning and losing has a huge impact. Many designers' self-worth is based on their job. You put so much of your heart and soul into it, and when somebody says they don't like it, it can all go black."

Paul agrees. "I think I've spent my entire career in a state of anxiety, constantly, and it doesn't really stop. Because there isn't a 'two plus two is four with design'; there's no end, is there? I remember when I was a junior designer, my stomach would just turn, sitting all day designing, running against the deadline."

To some extent, this kind of anxiety can be a good thing, keeping you motivated and on your toes. But it can become overwhelming and ultimately toxic.

"At some point, something's going to happen," says Paul. "You can't run at that speed forever." Yet the pressures that the industry is currently under are pushing us to do exactly that. Over my 20 years, briefs have been getting harder, timelines have been getting more aggressive, and some demanding projects have been so fast-paced that they're almost unachievable," says Paul.

Outside of the thinking about design, lose yourself in something. It could be crocheting or anything. Whatever it is, find that thing where you can turn off the voices. That's a really valuable thing to do.

Outside of the thinking about design, lose yourself in something. It could be crocheting or anything. Whatever it is, find that thing where you can turn off the voices. That's a really valuable thing to do.

Finding balance

So what's the solution? It starts, says Ben, with finding your centre. "It's such a cliche, but you need the right work-life balance," he says. "You put your energy and your heart and soul into your work, and we don't want people not to do that. But we also want them to be able to, for instance, come away from a loss, still feeling whole and complete."

Different people will have different coping strategies, but the important thing is for studio heads to support them, adds Ben. "For instance, we never criticise people when they lose. We'll say something like, 'Hey, you win some, you lose some; it's fine. We're probably too busy to take on more work anyway…'"

They also encourage their designers to take a broader view of their work rather than seeing it as a binary dynamic of success versus failure. "We all go down a rabbit hole when designing," says Ben. "But you also need to step back to have a big, helicopter view of life. Recently, I've been teaching my kids about breathing and how we all forget to breathe. It gives you time to think, relaxes the brain, and stops you from panicking or feeling bad or anxious."

Being comfortable in your skin

Paul and Ben also try to convey to younger designers that you don't need to be perfect. Indeed, they stress that despite their years in the game, rather than attain perfection personally, they've just learned to live better by not being perfect.

"Nowadays, I'm just comfortable with myself and my failings," says Paul. "For instance, when you present a client, and you're really in your head: you're ahead of yourself in a sentence, trying to think of the words that sound impressive. I used to do that a lot more when I was younger. But now I'm more real and relaxed, and I don't beat myself up for tiny, meaningless mistakes."

"I think rather than grace under pressure, it's about having perspective under pressure," adds Ben. "Just because a presentation doesn't go 100% right doesn't mean you're a 'bad designer', and it will definitely not ruin your career."

Finding focus

Ironically, he notes, men often love doing activities that create more pressure. "For instance, I snowboard and windsurf. Doing things at the extreme, that possibly have an element of danger, demands focus, and it makes you realise that all this other stuff is more in your head than in reality."

Paul offers a similar perspective. "I love track riding on motorbikes because it requires so much focus, lap on lap, to get better, quicker, and faster. You can see the quantifiable progress, but there's also zero room for any other thoughts. And that's mindfulness, isn't it? It can be doing something other than yoga or meditation. It can be anything where you give yourself the focus.

"So I'd say to any designer, no matter what gender, make sure you have that," he concludes. "Outside of the thinking about design, lose yourself in something. It could be crocheting or skydiving or anything. Whatever it is, find that thing where you can turn off the voices. That's a really valuable thing to do."

What we can all do

However, Paul and Ben are keen to stress that all of this shouldn't be on the individual. As a community, the design industry needs to unite and encourage each other to share their thoughts and feelings in a safe and supportive environment.

"The hope is by sharing the challenges we've faced as creative leaders, we can help designers, of any gender really, have the courage to speak out and seek out the support they need," says Ben. "Let them know there are strategies and communities available to help them cope and combat the pressure and anxiety that comes with having a career in creativity. And maybe, by having those honest, real conversations, we can all start feeling just a little bit better."

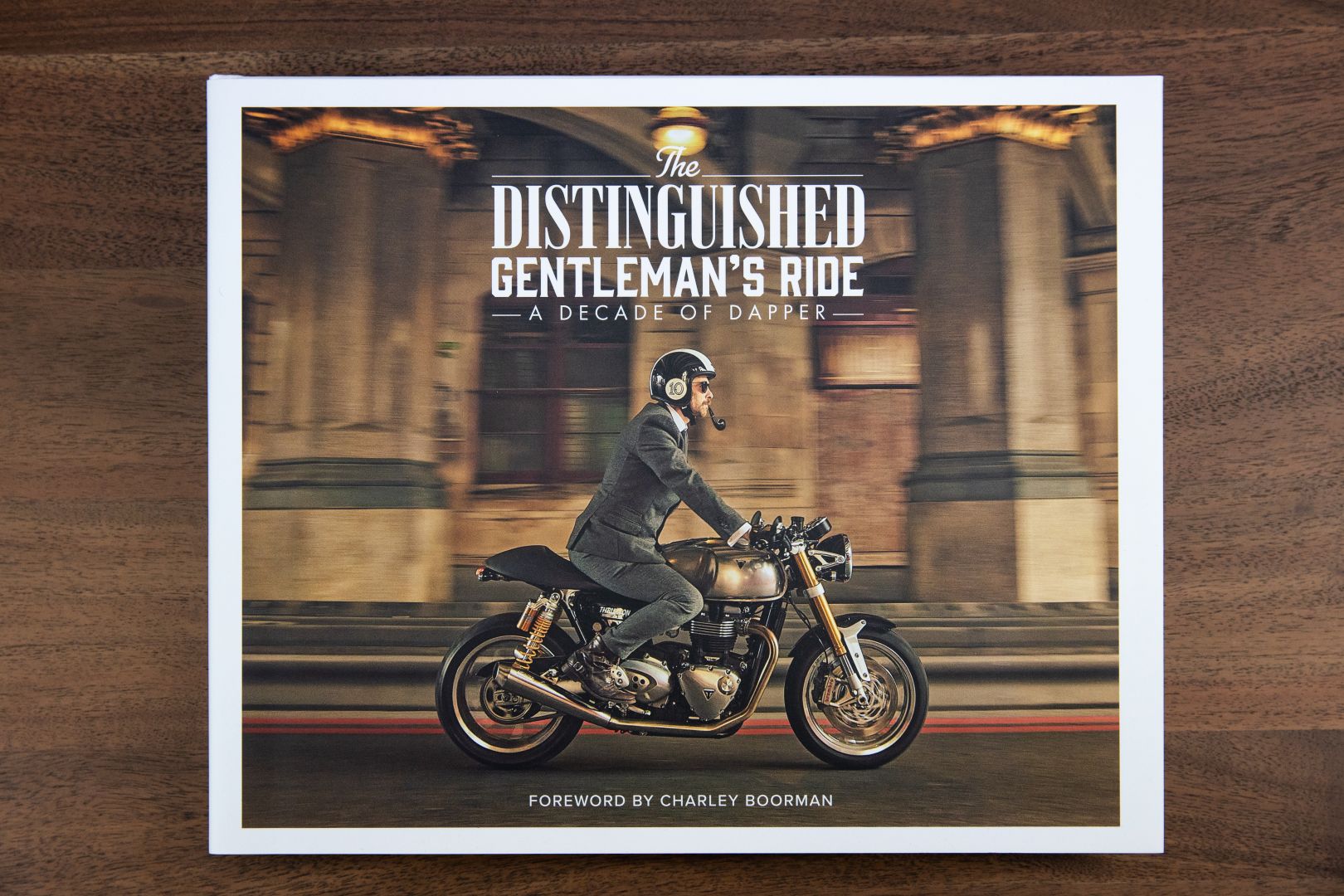

And if you want to go further, of course, you can also use your design skills to promote mental health. Paul's been doing just that as a supporter of The Distinguished Gentleman's Ride, which unites classic and vintage style motorcycle riders all over the world to raise funds and awareness for prostate cancer research and men's mental health.

In 2019, he drew by hand over 200 sketches of people's bikes and cars for £50 a piece and raised £11,154.52. As one of the top 10 fundraisers out of 121 countries and over 370,000 riders, he's recently been published in a book by the Movember Foundation celebrating the organisation. You can learn more and buy copies here.

Source: Creativeboom.com